By Joe Cerniglia

On July 5, 2017, during the second "In Search of Amelia Earhart" trip to Nikumaroro organized by Betchart Expeditions, trip member Karla Borde was working alongside a group of seven (including the author) when she discovered, wedged between a dried coconut and a wood fragment, the crushed, abraded and punctured casing of a 2-cell bullet-style flashlight. This flashlight was found on the surface of the ground within a few dozen meters of other artifacts near the old village dispensary.[1]

Photo #1: The flashlight in situ

Photo #2: The flashlight in situ with scale (coconut having been demolished in process of placement).

Measuring 7 1/16" in length, the flashlight's lens and lens reflector are entirely missing. The diameter of the circular end atop of which the bulb was seated measures roughly 3 1/2", having been distorted by some sort of impact. The flashlight weighs 90.82 grams. This artifact rested somewhere close to the side of, if not actually on, Harry Luke Boulevard, the main thoroughfare of the old colonial village, which once wended half a mile or more south to the newer village location and the boat landing. The casing is punctured in at least two places, crushed, creased and warped, and covered nearly uniformly with short abrasions and shallow marks, consistent possibly with ocean deposition as could be caused by a storm surge.

An Art Deco design of triple-fluted bands runs nearly the length of and surrounds the casing, which has a high gloss as would be found with chrome or perhaps nickel. Unlike many flashlights in the bullet style, this flashlight does not have a segmented detachable rear cap on the bullet end; rather, the casing is made of one piece. The batteries, therefore, would need to be installed from the front.

Photo #3: While the flashlight has retained much of its reflective brilliance, it is pitted with small scratches and puncture marks.

Photo #4: The flashlight is crushed, forming a lateral crease along its cylindrical axis.

Photos #5, #6, and #7: A large puncture hole appears on the switch side of the flashlight casing on the bullet end.

The Inscription on the Switch

The flashlight's switch plate is still present, but it is missing a slide or thumb-piece mechanism where only two recessed grooves now remain. A button on the switch is present but it is stuck in place. The switch carries an inscription:

PAT. DEC. 20, 1921

Photo #8: The dated inscription on the flashlight switch

The Patent

The patent to which the flashlight's inscription refers is U.S. Patent No. 15,249, a utility patent that was reissued on the inscription date (December 20, 1921) and that was originally filed on April 4, 1918 and granted as U.S. Patent No. 1,287,262 on December 10, 1918. The patent applicant was John T. Drufva of Longmeadow, Massachusetts, who filed as assignor to the Henry Hyman & Co., Inc. of New York, New York.[2]

This patent's key refinement to flashlight design was a dual control system for closing the circuit of the light by using either the button on the switch or the switch's sliding thumb piece. Pushing the button on the switch allowed for "flashing" the light, "as in giving signals." The slider, by contrast, allowed for "a more or less permanent or steady light" to be emitted from the flashlight.

Photo #9: The first page of the patent corresponding to the date on the flashlight switch.

Photo #10: The artifact flashlight's switch alongside its depiction in the corresponding patent drawing.

Date Range of the Flashlight: The Effective Term of the Patent

The patent is a utility patent. From 1861 to 1994, utility patents had a term of 17 years from the grant date.[3] Even though the patent is a reissue patent, having been reissued on a date three years later than the original patent, by law its duration did not extend beyond that allowed with the original grant date of December 10. 1918.[4] Therefore, the patent expired 17 years after the original grant date, on December 10, 1935.

At the time of this patent's issue, U.S. patent law, as set forth in Wilson v. Singer Manufacturing Company (1879), did not forbid the marking of patent information on products beyond the date of the patent's expiration. The presumption was that the relevant members of the public would be "presumed to know the law as well as the patentee" regarding the expiration date.[5] (Patent law in the 21st century has become more restrictive on this point.[6])

Even though the law permitted it, there was no legitimate reason to mark flashlights with this patent information beyond the date of December 10, 1935. The invention's protection had by then passed into public domain. Therefore, it would seem reasonable to presume that the flashlight found in the village was manufactured between 1921 and 1935, and no later than that date.

Photographs collected from the website of the Flashlight Museum appear to support this idea that the term of the patent and the manufacture dates of flashlights inscribed with this patent date coincide. Photographs of flashlights on this website show that certain models sold between 1928 and 1936 have the same inscription as the one found on Nikumaroro. None were found labeled as having been made or sold after 1936, or before 1928. The dates provided by this website, however, are meant only as a guide and would need independent corroboration from advertisements and trade literature to be absolutely certain of their accuracy.

Who Made the Flashlight?

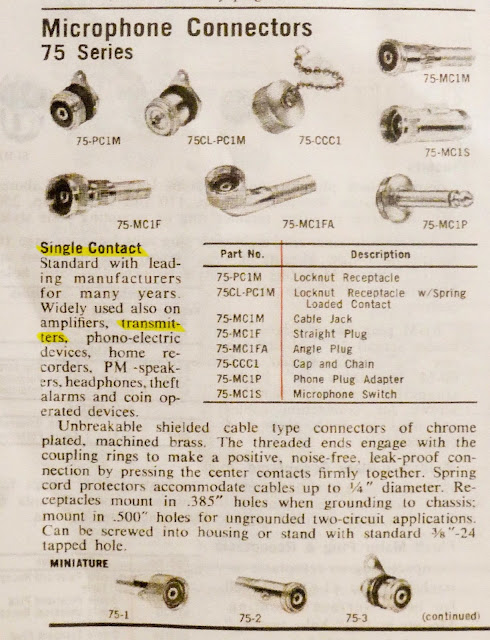

Based on the patent information inscribed on the flashlight, its manufacturer is believed to be the United States Electrical Mfg. Corp., maker of USALite brand flashlights. This belief is based on three distinct sources of information:

1) Henry Hyman, assignee of the patent, was president of the United States Electrical Mfg. Corp., maker of USALite flashlights.[7]

2) With one exception (Perko), the only flashlights observed to have had the same inscription and switch as the artifact were those branded as USALite.

Photo #11: Perkins Perko boat-mounted flashlights are the only flashlights thus far located other than USALite that carry the same inscription as the artifact.[8]

3) A flashlight advertisement from the 1930s confirms that USALite flashlights were using the switch described in U.S. Patent 15,249. The advertisement states the flashlight had a "3 point safety contact switch for continuous, signal lighting and complete shut-off."[9]

Photos #12, #13, and #14: USALite "Redhead" model with the same switch inscription as the artifact

Photo #15: 1930s advertisement for USALite "Redhead"

Admittedly, information regarding the manufacturing company of the flashlight adds little knowledge that the patent did not already provide. The patent already tells us the flashlight was a product of the United States and that it was manufactured in the 1920s or the 1930s. However, narrowing the flashlight's manufacturer to a single brand of a single company could perhaps aid additional future research in narrowing the exact production dates of this particular flashlight found on the island.

Photo #16: A letter on official company stationery from the United States Electrical Mfg. Corp.[10]

Who or What Brought this Flashlight to the Village?

Flashlights are enormously useful on Nikumaroro. Anyone who occupied or visited the island from 1921 to the present date in theory could have brought this flashlight to the village. There is no reason to exclude any particular person or group from consideration, although probabilities will, of course, vary.

Loran Unit 92: The Coast Guard (1944-1946)

An American Coastguardsman from 1944 to 1946 could have brought the flashlight. He would have been carrying a flashlight at least nine years old, but flashlights have been known to last this long. A flashlight might also have been a good gift for a Coast Guardsman to pass on to a colonist.

The Bushnell Survey Expedition (1939)

The U.S. Navy surveyors who visited the island in 1939 aboard the U.S.S. Bushnell to do map work would be prime candidates to have brought the flashlight. An American in 1939 carrying a 1921-1935 flashlight made in the U.S. is an entirely plausible proposition.

The Nikumaroro Colony (1939-1963)

A 1939 inventory of "Goods in hand" drafted by the British colony's first officer-in-charge, Gerald Gallagher, shows two entries for "Torches A and B."[11] Torch is, of course, the British term for flashlight. While one might expect flashlights on Nikumaroro brought by the colony to be British in origin, it is not beyond possibility that American flashlights might have been stocked in the Gardner Island Co-operative store, or that a colonist could have been given the flashlight by a Coast Guardsman or found it in the Coast Guard Loran station after its abandonment in 1946.

The Norwich City (1929)

The British freighter Norwich City ran aground on the island in 1929. Again, while we would expect flashlights aboard this ship to be British in origin, an American flashlight may have been welcome if it was available. The date on which the ship came to grief is positioned exactly midway between the flashlight patent's grant and expiration dates.

Amelia Earhart (1937)

The Luke Field inventory, documenting the equipment aboard the Electra on the first world flight attempt, lists several flashlights.[12] They include:

2 Two-Cell Eveready Flashlights

1 Small 2-cell Flashlight, made in Japan and

1 Pencil type flashlight

Four flashlights were thus carried aboard the first world flight attempt of the Electra. It may be presumed that some were carried aboard the second attempt.

While none of these flashlights corresponds to the one found on Nikumaroro, that does not preclude the possibility the flashlight found on Nikumaroro was from the Electra. Obviously, a working flashlight is practically a requirement for any airplane pilot, even today.[13]

Conclusions

The term of the U.S. patent on the flashlight places it well within range of Amelia Earhart's world flight, but nothing would have prevented the U.S.S. Bushnell survey crew or the Coast Guard or a raft of others as a depositional source. The artifact cannot by any means stand alone as a smoking gun to the Earhart mystery, but it is without a doubt intriguing, especially to those of us who collected it.

Question for Further Research

Can a sibling USALite flashlight be located that would enable us to pinpoint the date range of the artifact's manufacture more precisely?

__________________

Endnotes

[1] Here is a list of artifacts found near the old village dispensary in 2017, in addition to the flashlight:

3 or more folded circular foils (thick but pliable aluminum)

1 heliarc-welded aluminum tray with i-beam support slats

1 Westclox clock movement from the 1950s

Squarish bottle fragments, clear and green

1 small tea plate with dividers and fleur-de-lis design

1 aluminum belt buckle

1 boot with 16 brass eyelets (some missing)

1 cosmetic cap for a Bourjois (Paris) jar

Assorted corrugated iron debris and wooden posts

1 Tri-Sure fuel drum plug

Photo #17: Map of all artifacts found in the old village in 2017

Photo #18: Map of artifacts superimposed on the old village. Superimposition courtesy of Dr. Richard Pettigrew

[2] John T. Drufva, inventor; Henry Hyman & Co., assignee. Portable electric light. U.S. Patent 15,249. Filed November 8, 1920 and reissued December 20, 1921. Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office, Vol. 293, p. 577.

[3] "A Brief History of the Patent Law of the United States." Ladas & Parry. 19 Nov 2018. https://ladas.com/a-brief-history-of-the-patent-law-of-the-united-states-2/

[4] Charles B. Mann. Handbook of Patent Law for Patent Owners. Baltimore: Mann & Company, 1884, p. 49.

[5] Josiah Hooker Bissell. Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit and District Courts of the United States: For the Seventh Judicial Circuit. Vol. 9. Chicago: Callaghan and Company, 1882, pp. 173-177.

[6] "Using Expired Patent Numbers with Your Products Could Lead to Devastating Financial Losses." Davi and Kuelthau, Attorneys at Law. https://ono4p174nkhs68n5le94wblf-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/ExpiredPatentNumbers.pdf 20 Nov 2018.

[7] Obituary: Henry Hyman, 84, Founder of Noma Light Concern. 23 Dec 1970. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1970/12/23/archives/henry-hyman-84-founder-of-noma-light-concern.html 3 Jul 2018.

[8] "Perko, Marine Lamp." Worthpoint. https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/vintage-perkins-perko-marine-lamp-1790063824 19 Nov 2018.

[9] Provision of this advertisement was made possible by the work of Jim Roan, Librarian and Archivist at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. on 2 Oct 2018.

[10] Provision of this letter was also made possible by the work of Jim Roan, Librarian and Archivist at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. on 2 Oct 2018.

[11] Gerald Gallagher. Gardner Island Co-operative Store Statement for Year Ended Dec. 31, 1939. https://tighar.org/Projects/Earhart/Archives/Documents/Tarawa_Archives/1939_Co-op_Store/1939Co-opStore.html 20 Nov 2018.

[12] Luke Field Inventory. https://tighar.org/Projects/Earhart/Archives/Documents/Luke_Field.html 10 Oct 2018.

[13] Richard L. Collins. "The Night the Lights went Out." Flying Magazine, March 1988, p. 25. 28 June 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=5wvChb_1tvAC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=the+night+the+lights+went+out+flying+magazine+march+1988&source=bl&ots=KUhlHpm84t&sig=egCLuy97oHSyRP-1bT3v_cxn530&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjR-fjkmeTeAhUuooMKHSDRCCUQ6AEwAHoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=the%20night%20the%20lights%20went%20out%20flying%20magazine%20march%201988&f=false